Realistic Expectations

We can’t realistically protect our kids from everything, and there is value in a controlled exposure to the broader world. The Internet is a place containing anything and everything and is becoming easier and easier to access. If, as parents, we deny access to our children, they will eventually find it elsewhere as access becomes ubiquitous: at a friend’s house, at a coffee shop, or from a non-techy neighbor with an open access point. The best we can do is introduce them to the Internet gradually and construct sufficient safeguards to make it less likely for them to accidentally stumble into something awful and make it harder for predators to reach them.

There are many mechanisms and services out there for limiting access to the Internet, each with varying degrees of effectiveness, complexity, and maintenance requirements. Parents are increasingly busy and the Internet is increasingly vast and dynamic. We simply cannot be expected to approve every useful site for access, or worse, block every undesirable site.

Unfortunately, the easier something is to maintain for parents, the easier it is for a clever child to circumvent. In this article, I’ll focus on preventing accidental exposure to undesirable content, as opposed to Orwellian networking policies. We cannot control their access to the Internet much beyond the age of 12 (sic), so let’s teach them good principles in a safe environment so they are better equipped to make good choices when the training wheels come off.

Basic Networking

If you are unfamiliar with the concepts of Internet Protocol (IP) [1] and Domain Name System (DNS) [2], I encourage you to review the linked Wikipedia articles for a basic introduction.

In short, there are four principle concepts you should be familiar with: name, address, port, and protocol.

The name, http://google.com, is an alias to a real location, the IP address 74.125.228.226. Try clicking on the two links, you’ll find they open the same page. You can think of this in terms of “John’s House” and “1234 Main St, Metropolis ST, 55000”. If you don’t know where John lives, you will have to look it up. When you attempt to go to http://google.com, your computer first asks a DNS for the IP Address, which returns 74.125.228.226. The IP Address is formed from four 8-bit values called octets, which can be any number between 0 and 255. IP Addresses can be self-assigned by devices according to the rules of the network (called a static IP Address), or they can be requested by the device and assigned by a service running on the network called Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP).

Networks are a set of IP Addresses that can talk directly to each other. For example, the 192.168.1.0/24 network describes all IP Addresses between 192.168.1.1 and 192.168.1.255. The 24 indicates that the first 24 bits, three octets, of the network address are fixed and the last octet is used to identify the devices on the network. Devices on one network can only talk to devices on another network through devices called routers and bridges. In a typical home network, the router will have two IP Addresses: one on the public Internet assigned by an Internet Service Provider, and one on the Local Area Network (LAN) which is used to communicate with all the devices in the home. The router acts as a middleman who arbitrates all communications between all the devices in your home and the Internet.

In the http://google.com example above, the “http” term refers to port 80 on the server at the IP address. You can think of this a specific door at John’s house, while https on port 443 is a different door. Different services run on different ports, but technically speaking any service can run on any port.

Protocol is harder to put in common terms, but you can think of it as the means of transportation. You can ride a bike or drive to John’s house. On the Internet, the vast majority of traffic travels over TCP [3] and UDP [4].

If, for example, you didn’t want your children to access http://google.com, you could block that site using some service or application, but it may not prevent them from accessing http://74.125.228.226, which provides the exact same content. If you use software that filters traffic based on ports, it won’t be effective against websites running on alternative ports (many web services run on ports other than 80, and sites deliberately looking to circumvent your security measures will certainly consider this option). John’s Mom may have locked the front door, but she forgot about the bathroom window…

Finally, be aware that you likely have at least two points of access to the Internet in your home. The first is your broadband connection which your computers and laptops use, likely over Wi-Fi. The second will be your cellular devices with 3G or LTE data plans. While these device may use your Wi-Fi for a faster signal while in the home, they can easily be setup to use the cellular data network, bypassing any controls you have setup on your home router.

If you are concerned about the content your child has access to, consider limiting their access to Wi-Fi only devices in your own home. By the time they are old enough for a cellular data plan or a mobile Wi-Fi device, they will need to rely on the lessons you taught them at home to stay safe on the Internet.

Be sure to talk with your kids about why (not how) you are restricting their access, and use the opportunity to explore the good the Internet has to offer with them, while teaching them about the dangers so they can avoid them when they’re on their own (likely well before you think they’re ready).

DNS Filtering

With the goal of preventing accidental exposure, DNS filtering is a relatively effective way to limit your children’s access to the Internet. This works by checking each DNS request against a known-good list (whitelist) and a known bad list (blacklist). The address translation is only successful if the site meets your criteria. If a blacklisted site is requested, an alternate IP Address can be returned, informing the requester that the site has been blocked.

In order for this to be effective, the client machine (the laptop, tablet, etc.) will need to be configured to use the specified DNS servers. A clever user can simply replace these with non-filtering DNS servers, and they will have unfettered access to the internet. For very young children, this should be sufficient protection.

As they age and use their Google access to look for ways around your unreasonable limitations, you may need to take more draconian measures (such as DNS port-based DNAT to force all DNS requests for certain clients to specific servers - but that’s beyond the scope of this article).

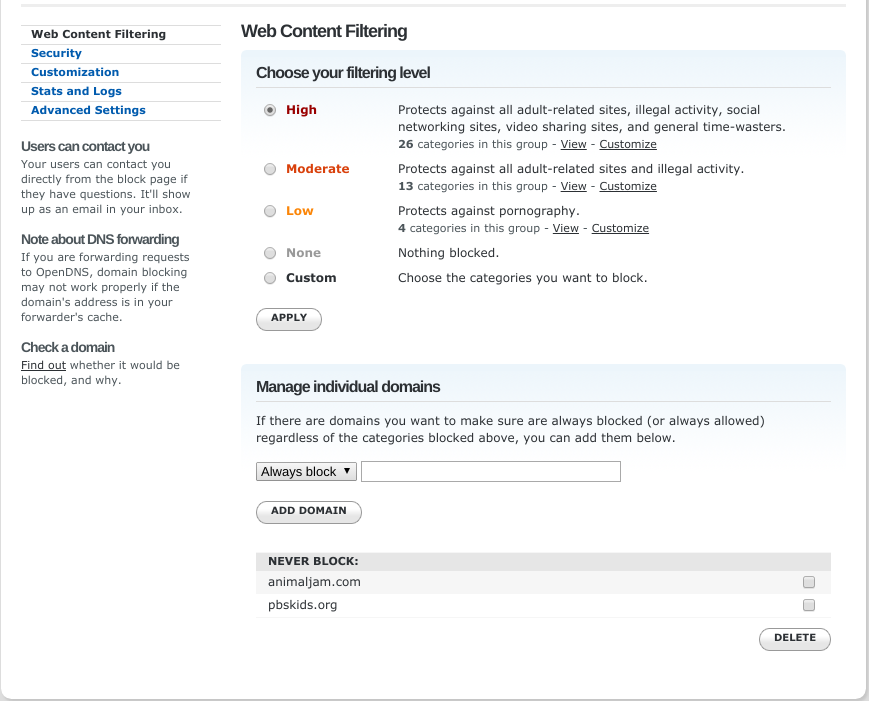

OpenDNS [5] offers a DNS filtering service with various pre-defined filtering levels and the ability to whitelist or blacklist specific sites. This offers the fine-grained control we want as parents, without the need to maintain the entire set of good and bad sites ourselves. OpenDNS is a very approachable service for non-technical people. To get started with this service, see their Parental Controls documentation. The free service is likely sufficient for most parents’ needs.

Once signed up, you can easily set the filtering level and manage individual domains (sites). In the example below, I chose the most restrictive level and added the two time-wasters my youngest immediately asked for after receiving the restricted content page:

VLAN Example

Depending on your level of filtering, you may not want the same rules applied to all devices in your home. You Tube and social media may not be appropriate for very young children, but we may still want to waste our own time there. To accommodate our hypocrisy, we need to use a different set of domain servers for the systems we use and the systems our children use. You can do this manually on each device, but it’s tedious, error prone, and makes it even more obvious how to circumvent it.

The term LAN refers to a Local Area Network, such as a network of computers isolated from the Internet behind a router (all the computers and devices in your home for example). Historically, LANs were created through physical cabling, switches, and routers. Wireless LANs (WLAN) are similarly isolated, but less obviously so due to the lack of the physical infrastructure.

A Virtual LAN (VLAN) is a software described LAN running on top of a physical LAN or WLAN. A VLAN allows you to isolate certain machines from the rest of the LAN. In our case, we can use a VLAN to put the machines the children use on their own network which uses a separate DNS from the rest of the LAN.

Setting up a VLAN involves defining the numerical ID, then ensuring that each component in your network is aware of the VLAN and will allow traffic to flow between them.

This example from my home network uses Ubiquiti networking equipment, including:

EdgeRouter Lite

My primary LAN network is 192.168.1.0/24, and uses the Google DNS [6] servers by default, with a third fallback to the DNS provided by my Internet Service Provider (ISP):

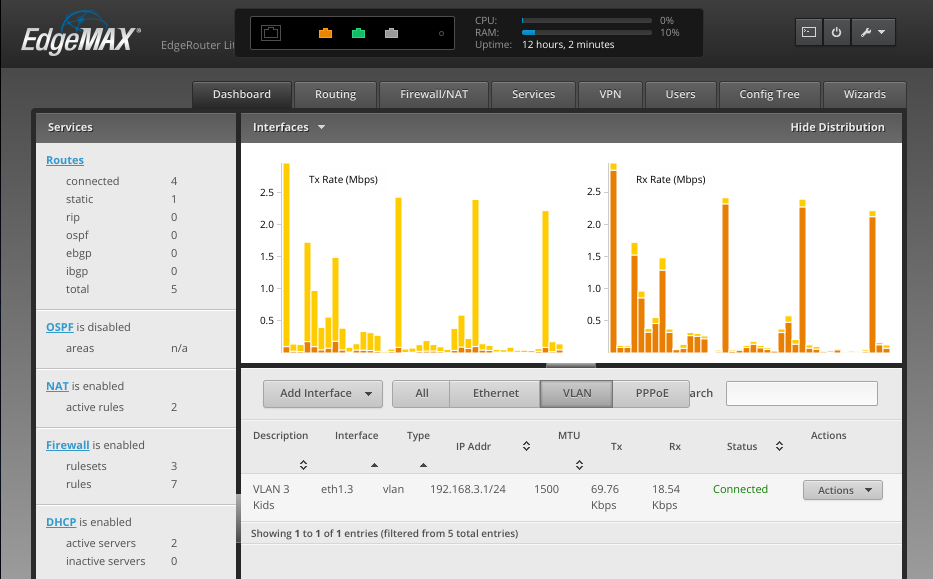

In my example, the protected VLAN ID is 3, and I create a second internal network 192.168.3.0/24 exclusively for it.

VLANs and networks do not technically require a 1:1 mapping, but it is convenient conceptually to map a VLAN to a network. In my case, VLAN 3 corresponds to the 192.168.3.0/24 network.

When creating a VLAN, you need to ensure your router has an IP Address on that VLAN in addition to the IP Address it has on the primary LAN. It also needs to provide a DHCP server for that VLAN. The router is typically assigned the first IP Address on the network. In this case, 192.168.3.1.

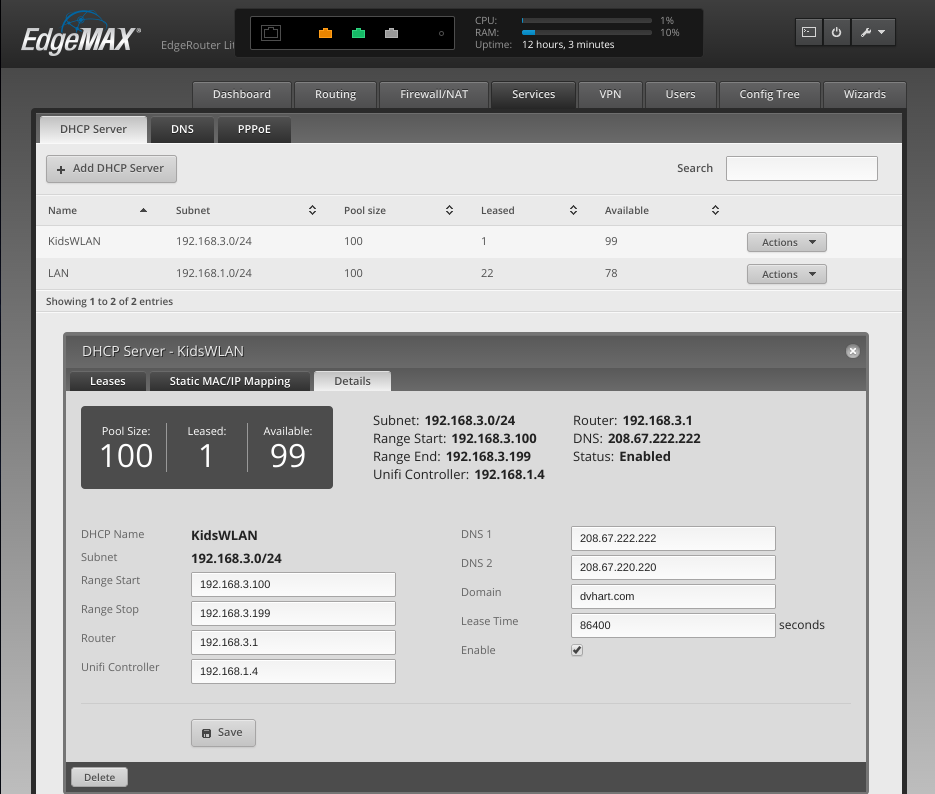

Next, I create a new DHCP server to service the 192.168.3.0/24 network. This assigns IP Addresses to the kids’ client machines and instructs them to use the OpenDNS servers (see DNS1 and DNS2 in the dialog box below).

ToughSwitch 5 PoE

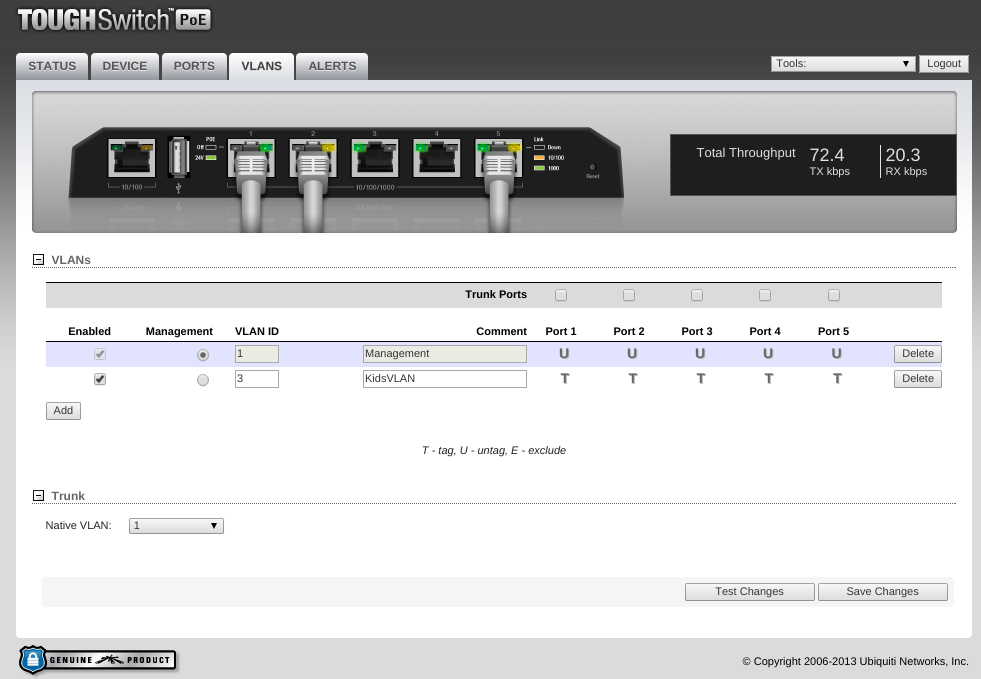

In my case, there is a managed Ethernet switch between my router and my wireless access points (AP). If your APs are connected directly to your router, you may have similar controls in your router’s administrative interface. If your APs are integrated with your router, you can likely skip this section entirely as there will be no ports to tag.

Whenever a VLAN passes through a switch, that switch needs to be told how to handle the VLANs. VLAN management is a complicated technical subject made all the more confusing by network equipment vendors using different terminology and mechanisms to accomplish the same thing.

Generally speaking, you need to configure your switch to allow the VLAN tagging to pass through the switch by enabling the VLAN on the port it arrives at and the uplink port to the router. In my case, I set each port to “T” (tag) for VLAN 3.

UniFi Controller

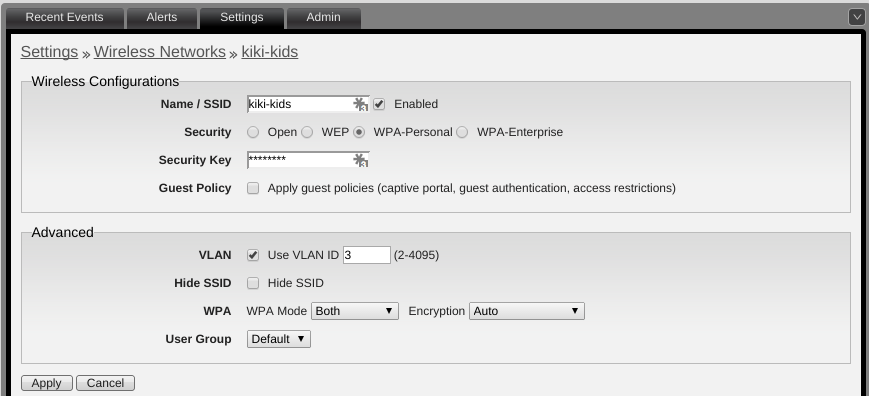

The kids connect to the Internet exclusively over Wi-Fi in our home, they have no access to hardwired devices. I can control how they connect by restricting those devices to a specific wireless SSID (the wireless network they connect to).

By creating a new SSID and assigning it to VLAN 3, they are isolated to the 192.168.3.0/24 network. This means as their machines request an IP Address from the router, they will receive it from the new DHCP server using the OpenDNS name servers.

After setting up the new SSID, be sure to “forget” the previous wireless network on all the kids’ devices. It’s a good idea to use a different security key for each SSID since if they were to connect to the primary SSID, the DNS filtering would no longer apply.

Alternatives

There are many approaches to filtering Internet content for children.

Supervised Users

This mechanism creates a special user account on the client device (laptop) which has locally imposed restrictions as to time allotment and Internet use. In our experience, these are very high maintenance, and are typically overly restrictive for inquisitive children.

Google’s Chrome Supervised User [7] allows the parent to whitelist individual sites via their Google account. Unfortunately, supervised users are not permitted to use Apps, which prevents children from taking full advantage of a ChromeBook. Secondly, the users have to managed individually as there is no profile management which can be applied to all supervised users.

Apple’s OS X also offers a similar mechanism for parental controls [8]. This proved to be painful in practice as well as high maintenance. Worse, it is limited in scope to the individual system. If you have multiple laptops, tablets, etc., this solution becomes unmanageable quickly.

Web Proxy / Cache

A more draconian approach to content filtering is to run what is called a web cache or proxy. All Internet requests on a specified set of ports are proxied through this service, typically running on another computer on your LAN, or on your router if you run higher-end networking gear. The proxy will examine the request and determine whether or not to allow communication to continue. This approach offers more control than DNS filtering, but requires a great deal more technical chops from the parent, now IT administrator.

Squid is a popular web cache / proxy which offers a plugin for such parental controls called SquidGuard [9]. The plugin reduces the maintenance effort significantly, but it’s still a rather advanced undertaking for most people.

Resources

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_Protocol

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_Name_System

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transmission_Control_Protocol

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User_Datagram_Protocol

- http://opendns.com

- https://developers.google.com/speed/public-dns/docs/intro

- https://support.google.com/chrome/answer/3463947?hl=en

- https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT201304

- http://www.squidguard.org/